It is very clear to me that the materialist world view as an absolute is limited. It works very well in our areas of focus, but leaves vast areas of existence and experiences unexplained – including consciousness.

The following article struck me as something I previously had not considered and is very strong evidence for a dualist or purely idealist view. I have been especially fascinated by the idealist world view as explored in a very rigorous & scientific fashion by Bernardo Kastrup.

As described In Mind Matters News, “in a podcast discussion with Walter Bradley Center director Robert J. Marks, neurosurgeon Michael Egnor talks about how many famous neuroscientist became dualists—that is, they concluded that there is something about human beings that goes beyond matter—based on observations they made during their work. Among them was Wilder Penfield (1891–1976) who offered three reasons for his change of mind”.

“Michael Egnor: Wilder Penfield was a neurosurgeon at the University of Montreal in Canada, who was really the pioneer in surgery for epilepsy. He worked back in the mid-twentieth century for several decades and he did surgery on probably upwards of about a thousand patients who had intractable epilepsy. They had seizures that couldn’t be controlled. He did brain surgery to remove the area of the brain that was causing the seizure to cure their seizures. And he did a lot of that surgery on patients who were awake during the surgery.”

Listen to the podcast on the page.

A partial transcript is here:

“08:25 | Penfield’s first line of reasoning for dualism

Michael Egnor: He started his career as a materialist. He thought the whole mind came from the brain and he was just going to study it. And at the end of his career, thirty years later, he was a passionate dualist. He said that there is a part of the mind that is not from the brain. He had several lines of reasoning that convinced him of that.

One line of reasoning was that, in mapping people’s brains—and again he mapped upwards of a thousand people this way—he would hundreds of individual stimulations of the surface of the brain to see what happened. And people would have all sorts of things happened. They would have their arm move or they would feel a tingling or they would see a flash of light. Or sometimes they’d have a memory or they would have an impediment. Sometimes they couldn’t speak for a minute or two after a certain spot was touched.

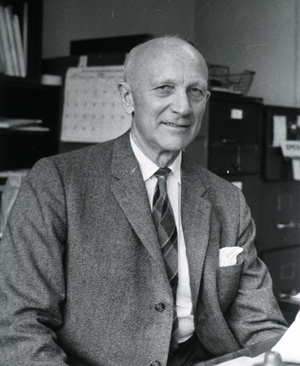

But Penfield (left, in 1958) noted that, in probably hundreds of thousands of different individual stimulations, he never once stimulated the power of reason. He never stimulated the intellect. He never stimulated a person to do calculus or to think of an abstract concept like justice or mercy.

All the stimulations were concrete things: Move your arm or feel a tingling or even a concrete memory, like you remember your grandmother’s face or something. But there was never any abstract thought stimulated.

And Penfield said hey, if the brain is the source of abstract thought, once in a while, putting an electrical current on some part of the cortex, I ought to get an abstract thought. He never, ever did. So he said that the obvious explanation for that is that abstract thought doesn’t come from the brain.

09:56 | Penfield’s second line of reasoning

Michael Egnor: The other line of reasoning that he had, which is kind of related to this, is that, since he was a pioneer in the treatment of epilepsy, not only did he study the surgical manifestations of epilepsy but he also studied the presentation of seizures that people would have in their everyday life. So he studied hundreds of thousands of seizures that people had and he never found any seizure that had intellectual content. Seizures never involved abstract reasoning.

When people have seizures, sometimes they have a generalized seizure. Sometimes they just fall on the ground and go unconscious. Or sometimes they’ll have what’s called a focal seizure where they’ll have a twitching of a finger or a twitching of a limb or they’ll have tingling feeling, the same kind of things that he got when he stimulated the surface of the brain. But nobody ever had a calculus seizure. Nobody ever have a seizure where they couldn’t stop doing arithmetic. Or couldn’t stop doing logic.

And he said, why is that? If arithmetic and logic and all that abstract thought come from the brain, every once in a while you ought to get a seizure that makes it happen. So he asked rhetorically, why are there no intellectual seizures? His answer was, because the intellect doesn’t come from the brain.

11:14 | Penfield’s third line of reasoning

His third line of reasoning was the following: He would ask people to move their arm during the surgery. So he’d be playing around with their brain. And he’d say. “Whenever you want to, move your right arm.” The person would move their arm.

And, once in a while, he’d stimulate the part of the brain that made the arm move. And they moved their arm also when he did that. And then he would ask them, “I want you to tell me when I’m making your arm move and when you’re moving your arm without me making you do it. Tell me if you can tell the difference.” And the patients could always tell the difference.

The patients always knew that when he stimulated their arm, it was him doing it, not them. And when they stimulated their arm, they were doing it, not him. So Penfield said, he couldn’t stimulate the will. He could never trick the patients into thinking it was them doing it. He said, the patients always retained a correct sense of agency. They always know if they did it or if he did it.

So he said the will was not something he could stimulate, meaning it was not material.

So he had three lines of evidence: His inability to stimulate intellectual thought, the inability of seizures to cause intellectual thought, and his inability to stimulate the will. … So he concluded that the intellect and the will are not from the brain. Which is precisely what Aristotle said.”